The Summer of Hate: Rise of Online Spaces as Battlegrounds

June 18, 2025‘The Intersection of Populism, Racism, and Misogyny’ by Zainab Dar

June 19, 2025Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest yet most marginalized province, endures not only physical repression but also systematic digital silencing. According to the Pakistan Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (COIED), over 10,000 enforced disappearances have been recorded across Pakistan since 2011, with at least 2,752 in Balochistan alone, and activists estimate the real figure may be closer to 7,000 missing individuals. In 2023 alone, the activist group Paank documented 576 disappearance cases, escalating to 619 in 2024, alongside rising extrajudicial killings and torture. Today, social media platforms have emerged as the new frontlines, where Baloch activists, especially women, face hate, disinformation, and censorship, just as sharply as they do offline.

While these issues have existed for decades, a new form of suppression has emerged in the digital world. Social media, once seen as a space for truth-telling and resistance, has now become another battlefield. Baloch activists, especially women, are not only silenced by the state but are also facing hate campaigns, disinformation, and content takedowns on platforms that claim to protect free speech.

Media Censorship and State Surveillance:

Being a journalist in Balochistan is one of the most dangerous jobs in Pakistan. Many journalists have faced threats, violence, and even forced disappearances, especially in high-conflict areas. Despite the risks, there is little to no protection for media workers or activists on the ground.

According to Amnesty International and other human rights groups, the situation for journalists in Balochistan has worsened over the years. Most attacks go unpunished, and those responsible are rarely held accountable. This failure by successive governments and the weak legal system has created a culture of impunity, where journalists live in fear but receive no justice.

One recent example is the killing of journalist Abdul Latif Baloch. On May 24, he was shot and killed inside his home by a state-backed militia in Balochistan. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) condemned his murder and called on the government to investigate the case. They demanded that authorities protect journalists and ensure they can work freely without fear of threats, violence, or harassment.

Sadly, cases like Abdul Latif’s are rarely covered by mainstream media due to state pressure and censorship. As a result, Baloch voices are often silenced and ignored on national platforms, leaving their stories untold and their struggles hidden from the rest of the country.

The Digital Escape: From Protest to Platform

As traditional media continues to ignore or suppress the voices of Balochistan, activists and the families of the disappeared have turned to social media to document their experiences and demand justice. Platforms like Twitter (now X), Facebook, and Instagram have become essential tools for raising awareness, organizing protests, and sharing stories that would otherwise go unheard. However, this digital shift has not offered the safety or visibility many hoped for. Instead, it has introduced new layers of censorship, surveillance, and algorithmic erasure.

The Double Standard of Social Media Platforms:

Baloch activists regularly use hashtags like #SaveBalochStudents, #BalochLivesMatter, and #StopEnforcedDisappearances to draw attention to ongoing human rights violations. These digital campaigns often emerge from grassroots movements led by students, families of missing persons, and rights defenders. Despite their peaceful nature, many of these posts are taken down, flagged, or shadowbanned without any clear explanation. Many Baloch activists have faced content takedowns, account suspensions, and shadowbanning, particularly when highlighting enforced disappearances, military operations, or student-led demonstrations. I’ve experienced this firsthand: my own account has been marked as ‘non-recommendable,’ significantly limiting visibility and engagement. This kind of digital silencing not only affects our reach, it erodes the very possibility of public accountability.

Many suspect that social media posts and livestreams by Baloch students protesting racial profiling and disappearances are reportedly taken down or hidden by algorithms, especially on Facebook and TikTok. Activist Sammi Deen Baloch has spoken out about being digitally silenced.

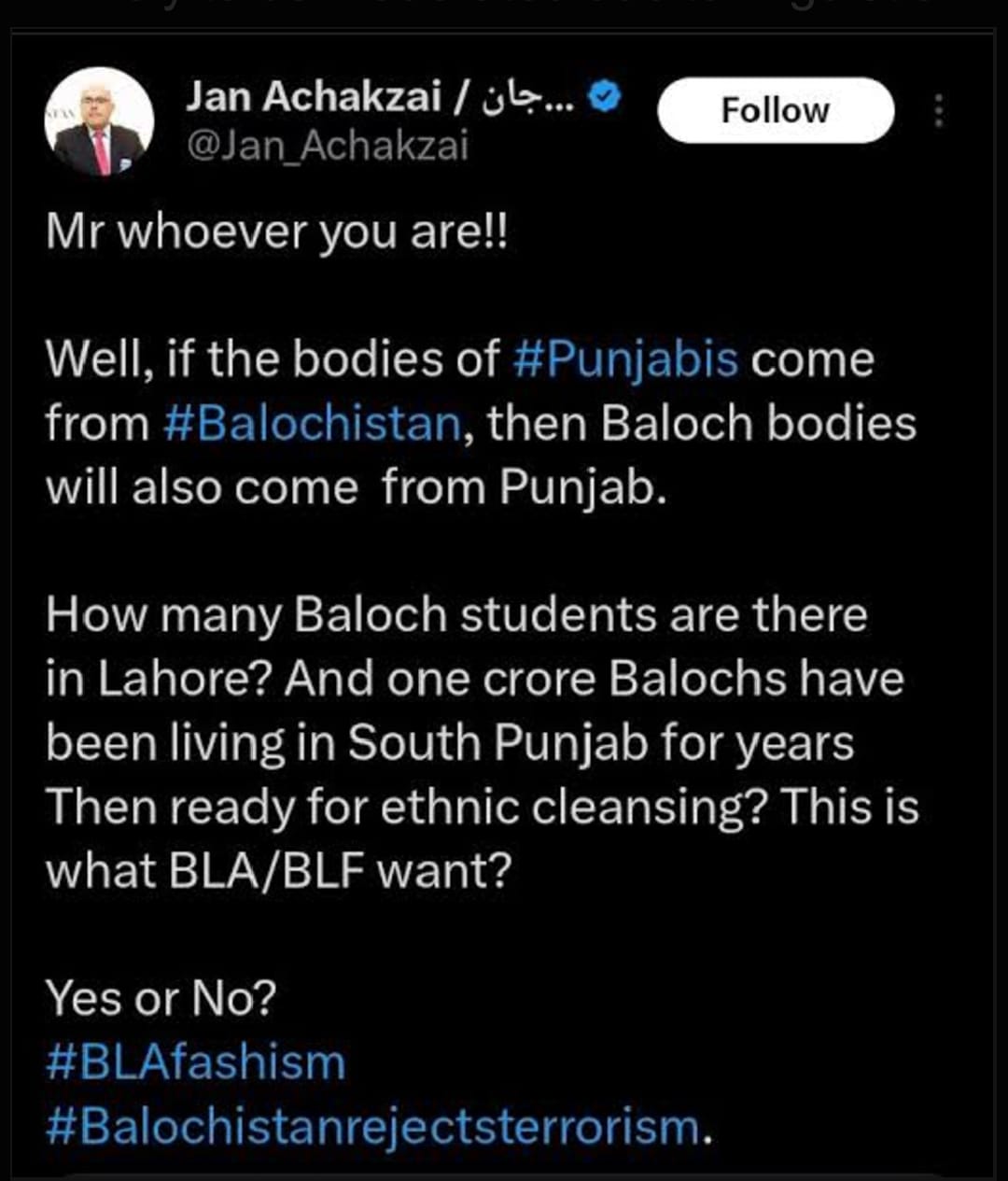

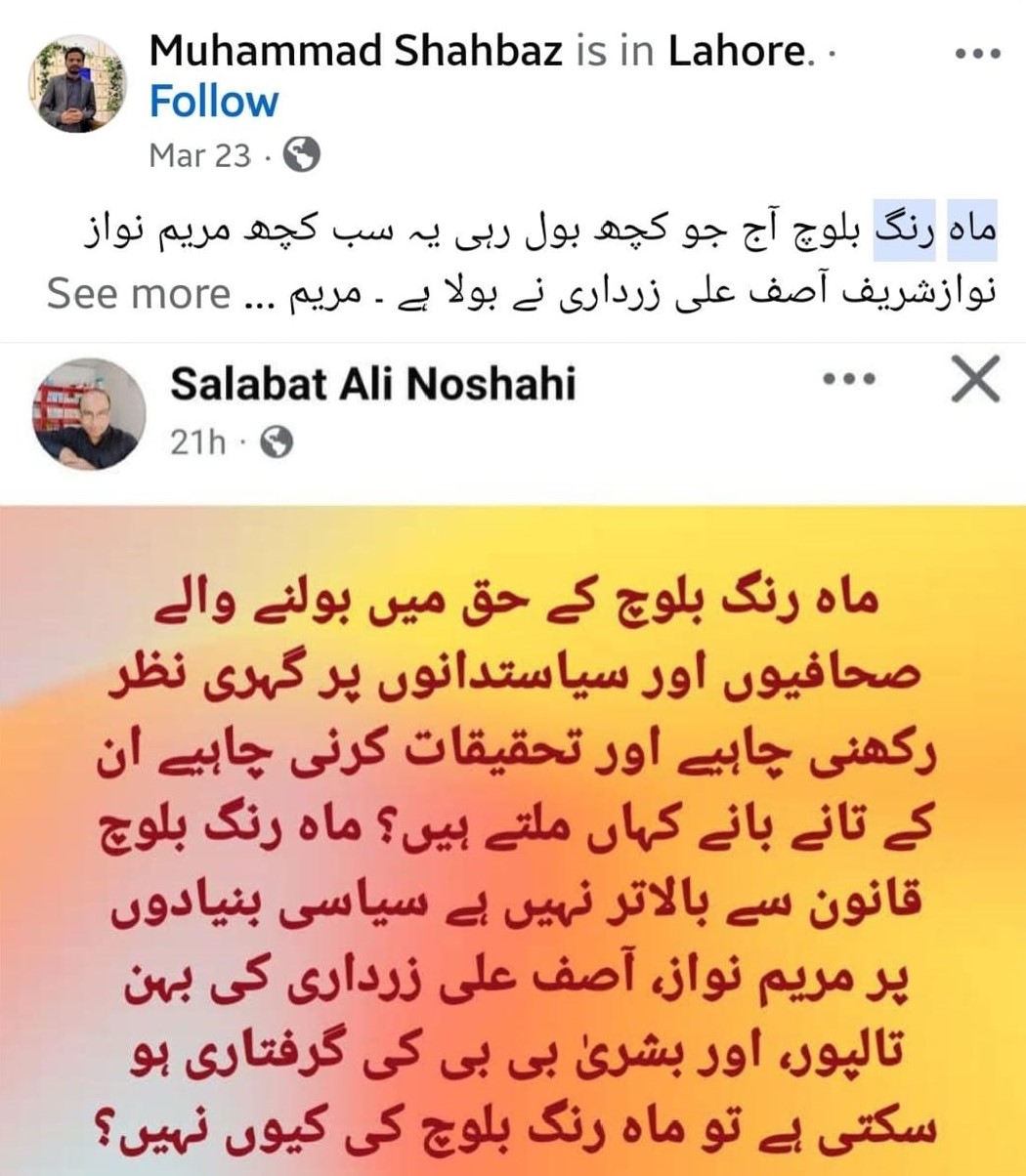

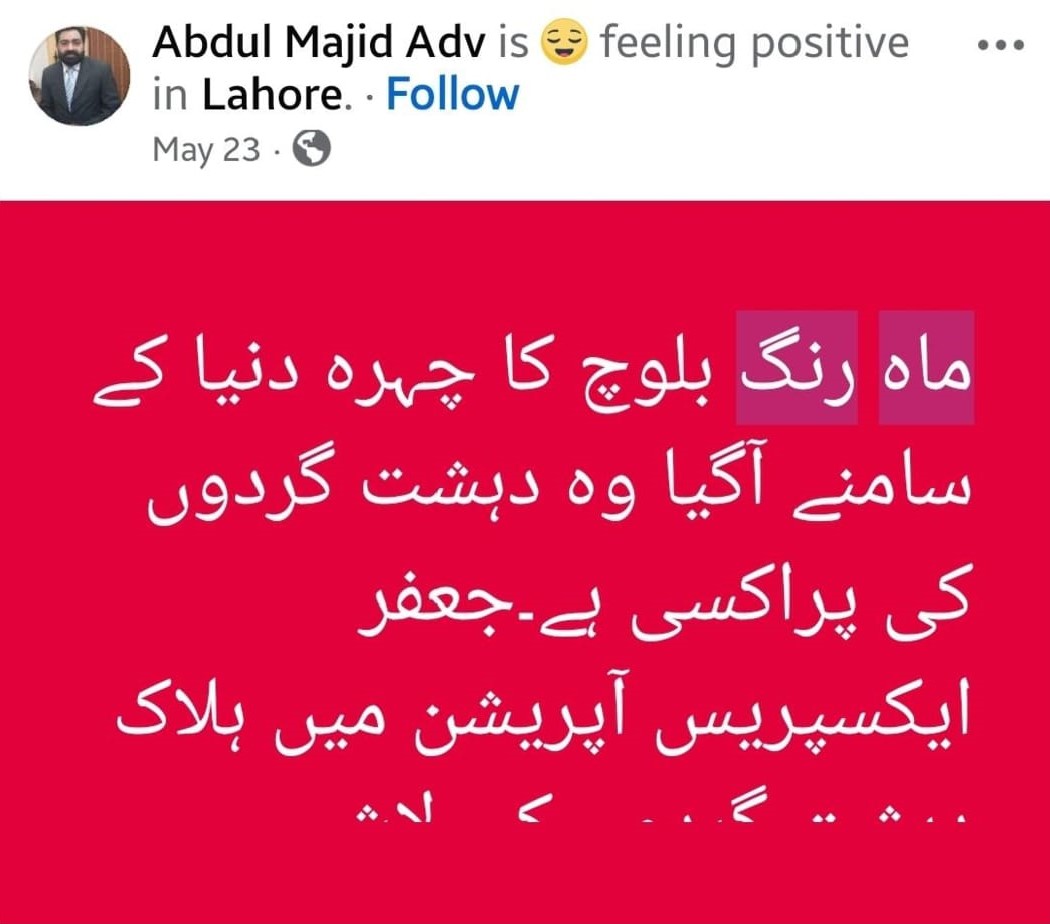

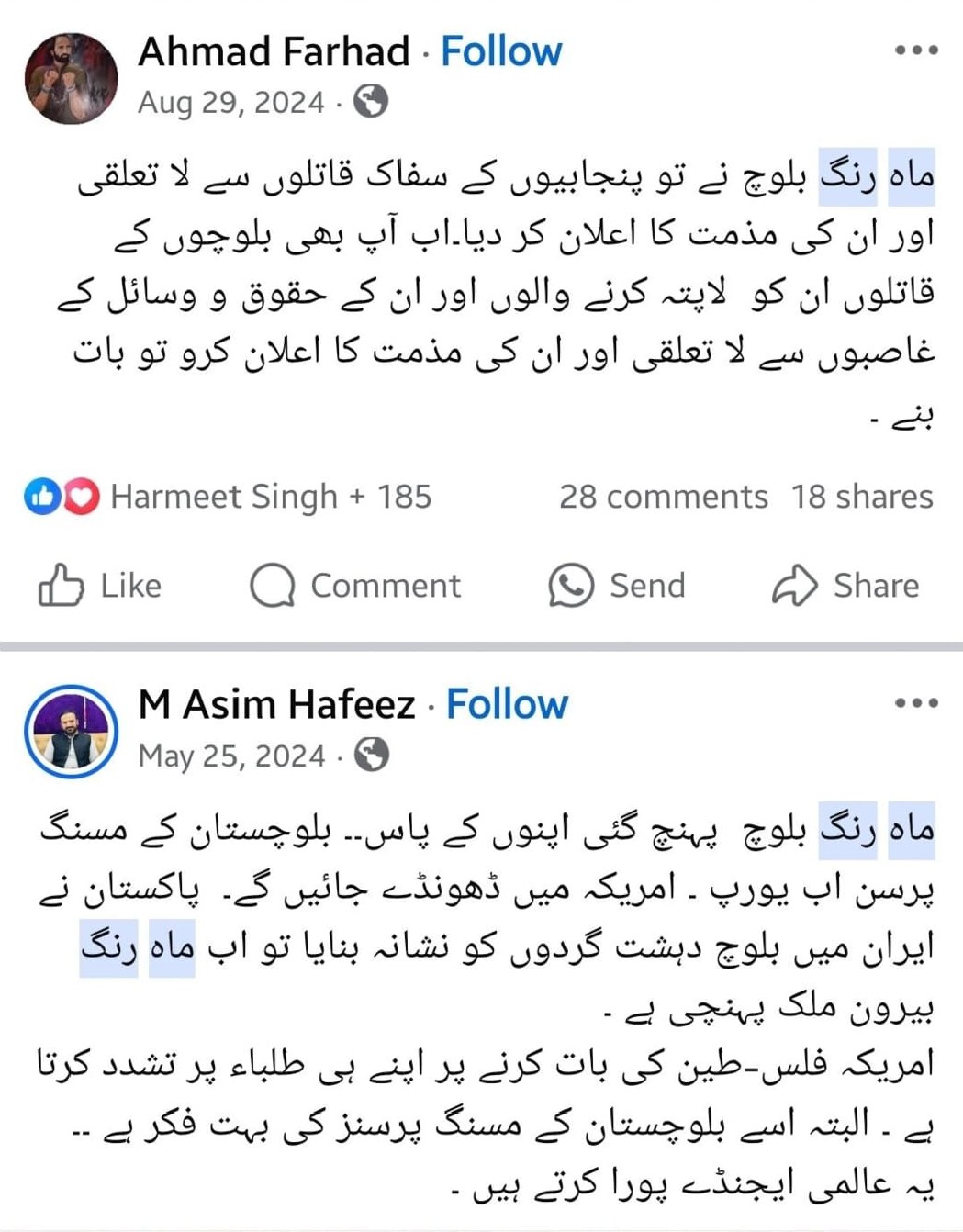

In stark contrast, posts promoting hate speech, racial slurs, or disinformation about Baloch people are rarely moderated. Many remain live for days or even weeks, gathering support and spreading harmful stereotypes. This creates a dangerous imbalance, where victims of violence and oppression are silenced while their attackers are given digital space to thrive.

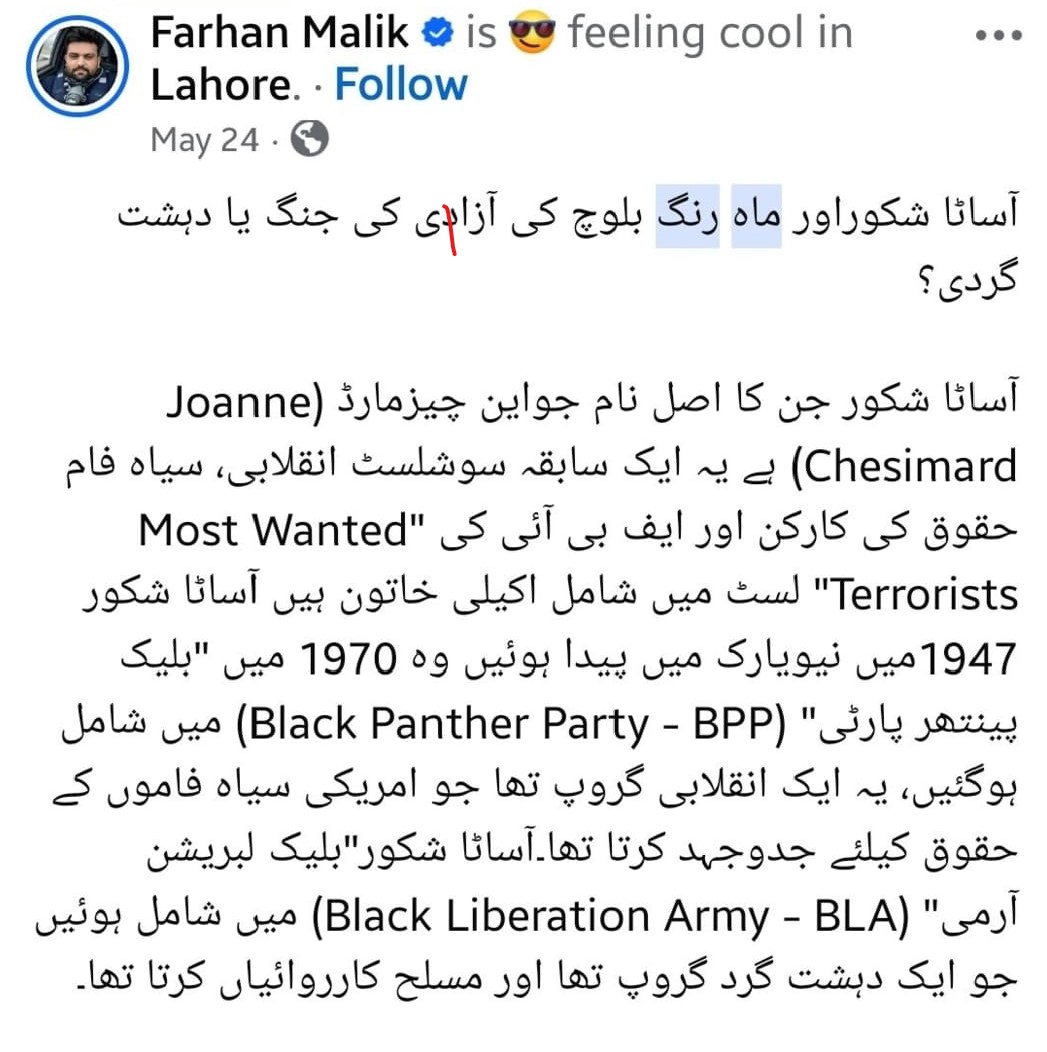

It has been observed that there has also been a surge in numerous videos accusing Baloch human rights activists of being “foreign agents,” “terrorists,” or “anti-state elements,” often using derogatory slurs such as “raw agents,” “traitors,” or “miscreants”. Despite being widely reported, many of these posts remained active. During protests in Islamabad (2021–2024), hashtags like #BalochDrama and #FakeAbductions trended, mocking enforced disappearances. Activists reported these, but X/Twitter did not take action in most cases.

Prominent Baloch female activists like Sammi Deen Baloch and Mahrang Baloch were targeted with gendered slurs and character assassination posts, many of which went unchecked to date. Several nationalist pages (still active as of 2023) regularly post manipulated images or conspiracy theories portraying Baloch protests as “foreign-funded chaos” or “extremist movements”. Posts written in local languages like Urdu or Balochi containing hateful speech are less likely to be moderated due to linguistic gaps in automated moderation systems.

Moreover, there appears to be a troubling regional disparity in how Baloch-related content is surfaced online. Activists have observed that when they log into X/Twitter from within Balochistan, their community’s hashtags trend locally, creating a sense of solidarity. But when the same accounts are viewed from cities of Punjab, Sindh, those posts are either invisible or deeply buried. This form of digital fragmentation not only weakens nationwide support but also allows state-sponsored disinformation to fill the void.

While no comprehensive data or comparative analysis currently exists to measure this algorithmic gap, several activists have shared consistent observations. For instance, two Baloch activists, Kinza and Awais, noted that when logging into X from Balochistan, community hashtags like #BalochMissingPersons trend locally, creating a visible sense of solidarity. However, the same hashtags often remain invisible or far less prominent when accessed from cities like Lahore or Karachi. While anecdotal, these repeated patterns point to a potential and alleged case of digital fragmentation, where regional visibility is restricted, unintentionally or otherwise, limiting national awareness and leaving room for competing narratives or disinformation to thrive.

Digital Disappearance of Truth and Surveillance:

Awais, a young activist from the Hazara community in Quetta, shared a heartbreaking experience that reflects this growing digital repression. One of his close friends, a young woman, was very vocal on social media platforms about the political climate in Balochistan. He added that, “She would post about disappearances and injustice, and we’d always tell her to be careful”. Awais recalled, “We begged her to stop posting. But she didn’t want to stay silent. She believed someone had to speak up.”

“One day, she just disappeared. We still don’t know where she is,” Awais said quietly. Her disappearance is part of a growing pattern where digital activism leads to real-world danger.

Awais also spoke about how hard it is to even see content about Balochistan online. “When I open social media, I see posts about Gaza and global issues. But Balochistan? Almost nothing. It’s like the algorithm hides it from people outside the region,” he said. “Even politically active people don’t know what’s going on because the posts don’t reach them.”

For Awais and others like him, the emotional toll is high. “We’re always paying the price for something we didn’t do,” he said. According to Awais, “People in Balochistan are tired. Young people just want to leave the country now. They don’t want to live in fear anymore, always worried that they or their friends might disappear just for telling the truth.”

Coordinated Hate Campaigns and Digital Censorship Against Baloch Activists:

Romasa Jami, a social activist and human rights advocate, says the crisis in Balochistan is not just ignored, it is intentionally erased from public discourse.

“There’s a conscious silence,” she explains. “Many people in Pakistan remain unaware, or choose to stay unaware of the serious issues in Balochistan. Most don’t even try to learn what’s happening.”

Romasa notes that Baloch activists, students, and human rights defenders are frequently bombarded with hateful and abusive messages online, simply for speaking out.

“They’re wrongly labelled as ‘anti-state,’ ‘foreign agents,’ or even ‘terrorists,’ just for demanding basic human rights. These labels are part of a systematic campaign to silence and discredit them.”

One of the more insidious tactics, according to her, is the weaponization of misinformation to create fear and suspicion.

“Some Indian media outlets push the false narrative that all Baloch people support India. This is then used within Pakistan to justify the state’s mistreatment of Baloch voices. It becomes a dangerous justification: if you talk about justice in Balochistan, you must be working for a foreign enemy,” said Romasa.

This disinformation, she adds, doesn’t just affect people who are misinformed; it also shapes perceptions, even among politically active citizens.

“People in urban areas, even those with higher education, reinforce these negative stereotypes. They don’t question them. It becomes nearly impossible for Baloch voices to be heard with fairness or empathy,” she added.

Romasa also shares her personal experience with digital censorship when she tried to speak out during the arrest of Dr. Mahrang Baloch, “I posted stories using hashtags like #FreeMahrangBaloch, but they were removed. My posts were shadowbanned. I didn’t even realize they were being hidden until someone pointed it out.”

In an effort to avoid further suppression, she had to reword her posts. She added, “I rewrote my captions using more careful, ‘acceptable’ political language, just to avoid triggering the algorithm. I still don’t fully understand how it works, but I know it’s real. And I know it’s working against us.”

Even with these precautions, she still faced backlash, “I received hateful messages. People attacked my character just for standing in solidarity with the Baloch community.”

Romasa emphasizes that this kind of harassment isn’t just emotionally draining, but actively discourages women from speaking up. “It creates fear. It forces many women to either stay silent or censor themselves. And that’s exactly what these campaigns are designed to do.”

Silencing of Baloch Women:

One young woman activist, who is particularly vocal on social media platforms, shared how her struggle for education isn’t just hindered by geography or poverty, but by a generational war against silencing. The disappearance of her brother and the constant fear of state backlash have shaped every part of her life and every Baloch woman’s too.

“It’s not safe to speak with my real name,” she said. “Our identities can kill us.”

Like many others, she uses altered names or remains anonymous online, aware that any visibility could put her or her family in danger. To be known is to be vulnerable. Even a single tweet, a photo at a protest, or a shared memory of a missing loved one can bring threats, harassment, or even state retaliation.

In Balochistan, women have become powerful voices in the fight against enforced disappearances and state violence. Many of them do not come from political backgrounds; they are mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters, but they still step forward to protest and demand justice. They take part in sit-ins, marches, and speak out online, even though doing so puts them at great risk.

Despite their immense courage, Baloch women are systematically ignored, not only by the state and mainstream media but also by Pakistan’s urban feminist spaces. Their daily protests against enforced disappearances, repression, and injustice are rarely covered on national news channels. Within popular feminist movements, their voices are often silenced, dismissed, or misunderstood.

“There’s a clear disconnect between urban feminists and grassroots Baloch women,” says Kinza Fatima, a Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies graduate from the University of Cincinnati and a native of Balochistan. “Urban feminists often view them as passive victims or ‘drama queens’ instead of recognizing their strength, leadership, and resistance.”

In spaces that should offer solidarity, Baloch women are routinely labelled as “agents,” “petty,” “immoral”. While urban feminists champion women’s rights in theory, many fail to stand with Baloch, Pashtun, and rural women from Sindh in practice. There is a lingering savior complex, where women from conflict regions are seen not as political actors, but as helpless figures in need of rescuing.

Kinza added, “Baloch women are often seen as the most suppressed, but they are, in fact, the most progressive. They are resisting militarism, patriarchy, and media silence, all at once. In a country that demands obedience from its women, Baloch women’s very existence as dissenters is revolutionary.”

Kinza Fatima further highlighted how, despite facing online censorship and threats, Baloch youth, and especially women, continue to find powerful and creative ways to resist. They use tools like poetry, digital art, anonymous storytelling, and symbolic imagery to raise awareness about the issues their communities face.

Because direct political statements are often flagged or removed by social media platforms, many Baloch creators choose to use symbols. For example, a picture of an empty chair, shoes, or a fading shadow might be used to represent a missing person. These quiet but powerful messages carry deep meaning, especially for families affected by enforced disappearances.

These artistic and symbolic expressions are mostly shared on platforms like Instagram, X, and Facebook. Some of the accounts posting this content have built large followings. They serve as digital community spaces where people can express their grief, share hope, and connect with others globally.

But this resistance is constantly under threat. Some of these accounts are mass-reported and taken down. Even when users try to appeal, most of the time their accounts are not restored. Years of emotional stories, digital artworks, and educational content disappear instantly, silencing not just the content creators but the voices of an entire community trying to be heard.

Before major Baloch gatherings or protests, we often face deliberate internet blackouts and telecom disruptions,” Kinza explains. “These aren’t just technical issues. They are intentional strategies to block coverage, disconnect us from the world, and prevent national and international solidarity. It’s a form of digital isolation that silences resistance before it even begins.”

This pattern of erasure makes it harder for Baloch youth to continue their advocacy and build solidarity with the outside world. Yet despite these barriers, they keep creating, keep telling their stories, refusing to be silenced.

The Problem with Social Media Moderation:

One of the biggest problems with social media platforms is the lack of understanding of the local political context. Posts that peacefully demand justice are wrongly removed, while hateful or violent content is allowed to stay up.

Most moderation is outsourced to other countries, where moderators may not know the actual issue or may have their own personal or political biases. This results in unfair treatment of Baloch activists, especially women, who are already vulnerable. When social media platforms fail to protect human rights defenders, it makes it easier for disinformation to spread and harder for justice movements to grow.

There is an urgent need for these companies to create localized, transparent moderation standards. Activists should not be penalized for reporting human rights abuses, while trolls who spread hatred and disinformation remain protected.

Tech companies must also publicly disclose when content is removed due to state requests, and they must offer better appeal systems to those affected.

Choosing the Right Side of History:

The struggle in Balochistan is not new, but social media has finally allowed parts of the truth to surface. Now, that truth is being pushed back again, this time not just by governments, but by algorithms and trolls.

Yet, people are beginning to listen. More users are becoming aware of the patterns of repression. Artistic content, digital campaigns, and personal stories continue to break through the barriers.

As Kinza says, “You don’t have to do something big: just choose to stand on the right side of history. Refuse to share false narratives. Refuse to ignore suffering.”

Baloch people are not asking for pity. They are asking to be seen, heard, and treated with dignity — both offline and online.