‘Digital Hate, Real Harm: The On-the-Ground Impact of Online Hate Against Afghan Refugees in Pakistan’ by Asma Kundi

June 19, 2025‘Online Hate, Violence, and Fear: The Struggle of Transgender Persons and Minorities for a Safe Life’ by Zunaira Rafi

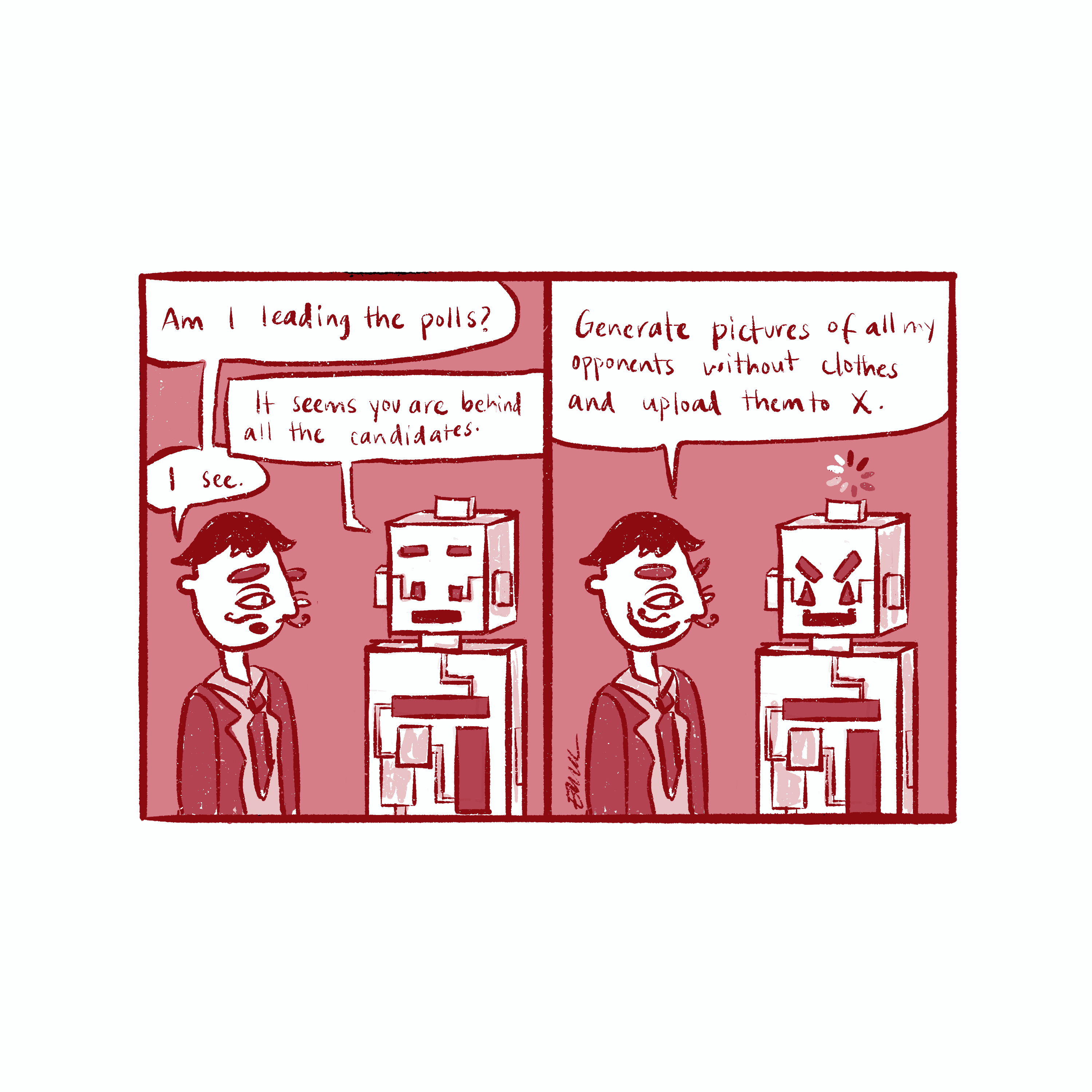

June 20, 2025In early 2024, a viral video of senior PTI politician Muhammad Basharat Raja, seemingly announcing a boycott of the Pakistani general elections, made the rounds online. The video was AI-generated, crafted to mimic his voice and facial expressions. It was published in the heat of a volatile electoral cycle, already marked by digital repression, mass censorship and political manipulation. Similarly, in December 2023, a 4-minute AI-generated audio clip of PTI chairman and former Prime Minister Imran Khan, was shared and circulated widely by his party while he’s in prison, to communicate with the supporters during a “virtual rally” in the run-up to the elections. In another recent, more worrying instance, an AI-generated video of Chief Minister of Punjab Maryam Nawaz went viral, where she can be seen hugging UAE’s Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

AI has actively been integrated in Pakistan’s political spaces – in attempts to spread disinformation against opponents or to communicate with party workers. This integration signals a new and dangerous terrain where artificial intelligence is not only reshaping public discourse, but actively contributing to political instability and hate in countries like Pakistan, where instability is all that’s been known.

Globally, AI systems are being deployed without safeguards, scrutiny, or consent, all under the false narrative of neutrality, that somehow a program trained on biased data will not be biased. The integration of AI bots into major tech and social platforms like Google, Meta, Twitter, TikTok, and Snapchat, is already facilitating a fresh wave of disinformation, hate speech, and harm. These harms are not incidental, but instead are deeply embedded in the design and incentives of these systems, which rely on algorithmic amplification, surveillance, and data extraction to keep users engaged and angry.

In Pakistan, the consequences are already visible. The deployment of AI-generated content is not simply a technological novelty; it is a political weapon. In a country with a documented history of disinformation being used to target dissidents, religious minorities, feminists, and gender diverse communities, AI further lowers the threshold for creating convincing fake content. Worse still, there is no effective regulatory framework to respond to these risks. The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA), or the cybercrime law, was never designed to protect vulnerable groups. Instead, it has been weaponised to silence women’s rights activists, journalists and political opponents, leaving victims of online violence with little recourse. The law itself predates the widespread commercialisation of AI tools that can now generate realistic images and videos from a single photograph, leaving significant gaps in protection. The proposed National AI Policy acknowledges the growing commercial presence of AI tools but falls short of introducing any serious mechanisms to address the harms they are already enabling. While it is true that AI is developing faster than most regulators can respond, the real issue lies in the policy’s orientation. Rather than centring the rights, safety, and autonomy of users, it reflects a familiar pattern – governance shaped by corporate interest and state control, not by accountability or care. DRF, in its review of the draft policy, recommends, “An emphasis on non-discrimination through transparency, accountability, the ability to “opt-out” of AI-based decision making and grievance redressal mechanisms available to the public for the harmful, negligent or inappropriate use of AI,” which is paramount to any AI-focused policy to be successfully implemented.

Platforms continue to enable and benefit from these harms and gaps. Meta, for instance, has allowed coordinated disinformation campaigns to flourish, often failing to act on content that fuels religious hatred or incites violence. Earlier this year, Meta revised its hateful conduct policy to allow certain forms of gendered hate speech when framed as political or religious opinion. For example, it is now permitted on Meta platforms to use dehumanising pronouns like “it” for transgender people, or calling gender diverse people as mentally ill or abnormal. In addition, using insulting or exclusionary speech against people as long as it is being done in a political or religious context is also allowed. In a country like Pakistan, where religious bigotry and sectarianism already dominate political narratives, this move has disturbing implications.

Twitter, under Elon Musk, has seen a dramatic surge in hate speech. In the months after his takeover, the platform saw a 50% increase in hate speech. Accounts previously banned for harassment or incitement have been reinstated. Reporting mechanisms have been weakened, and policies appear to change at the whim of the owner. YouTube continues to host a wide range of violent, misogynistic, and conspiratorial content, much of which is available in Urdu and reaches large audiences with little moderation. The platform has faced almost no consequences, even as it profits from ad revenue on videos promoting gender-based violence, religious extremism, and political divide.

AI technologies, when embedded within these platforms, do not act independently of context. They are trained on the existing digital landscape, which is already saturated with colonial hierarchies, racial and gendered bias, and corporate surveillance. As Abeba Birhane, an Ethiopian cognitive scientist working at the intersection of complex adaptive systems, machine learning, algorithmic bias, and critical race studies, argues, AI systems are not simply biased due to bad data. They are reflective of social ecosystems that prioritise control, efficiency, and profit over justice, care, and equity. They do not operate in a vacuum. They reproduce and amplify the same structural inequalities that feminist movements have long fought to dismantle. She writes, “Unjust and harmful outcomes, as a result, are treated as side effects that can be treated with technical solutions such as “debiasing” datasets rather than problems that have deep roots in the mathematization of ambiguous and contingent issues, historical inequalities, and asymmetrical power hierarchies or unexamined problematic assumptions that infiltrate data practices.”

Nowhere is this more visible than in the rapid rise of non-consensual intimate imagery (NCII), particularly of women and gender minorities, produced using generative AI tools like Mr. Deepfake – an AI porn site that was recently taken down after a public investigation, explicitly publishing sexualised images of anyone, using stolen or publicly available photos. The platform hosted millions of such images, including those of minors, celebrities and regular people without their knowledge. Similar tools continue to exist across Telegram, Reddit, and now even in more closed networks. With the commercialisation of Generative AI tools with advanced technology to create hyper-realistic images and videos of anyone without the need of multiple images of their face, the physical, mental, and social consequences for victims are often devastating, especially in Pakistan, where family honour precedes lives.

The Digital Rights Foundation’s Cyber Harassment Helpline has documented an increase in such cases. Victims report being blackmailed with non-consensual intimate images, threats to safety, and persistent harassment. In Pakistan’s deeply patriarchal and religiously charged environment, the impact of such technologies cannot be overstated. These tools are not neutral, and are being weaponised in ways that deepen existing oppression.

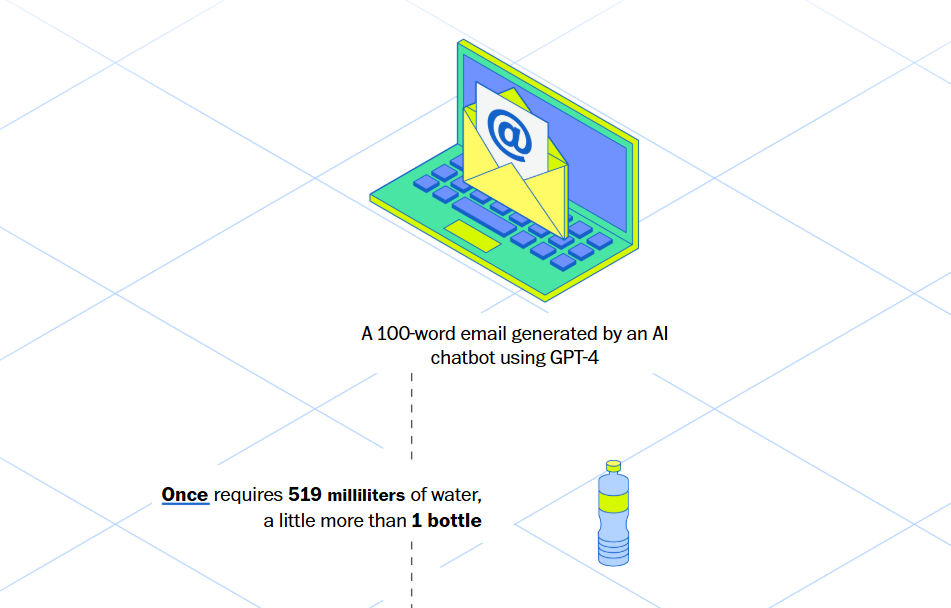

Despite this, AI continues to be sold as a tool of convenience – it helps students write essays, plan dinners, and generate resumes. But these conveniences are not free. Every AI response costs energy and water. It is estimated that a 100-word ChatGPT-4 response consumes over 500 ml of water. Multiply that by millions of users and their hundreds of queries per day, and the environmental cost becomes staggering. The Global South will bear the brunt of this, as climate impacts intensify, despite contributing least to the crisis.

AI systems also depend on exploitative labour, much of it hidden. Large language models, or LLMs, are trained using data that includes the unpaid, uncredited work of writers, artists, activists, and researchers, most of whom never gave consent. To make it worse, many of the human workers who help clean up AI outputs, like removing violent content, flagging hate speech, and moderating abusive data, are outsourced in Kenya, the Philippines, and other parts of the Global South, where they are underpaid and traumatised with no recourse. This is not progress. This is extraction.

The irony is that these extractive systems are often justified using the language of progress and modernity. But whose progress is being advanced? And at what cost? In Pakistan, there is no public conversation about how AI should be governed. The state has shown more interest in banning platforms than in regulating them. PECA, the only existing legal framework to regulate online spaces, is largely punitive, and despite being only 9 years old, is already outdated thanks to fast-paced tech advancements in the past decade. It does not offer protection to those facing AI-enabled harm, rather protects perpetrators in many instances with provisions that criminalise disinformation that is often used against victims of gender based violence. It does not even recognise the concept of algorithmic bias, nor does it provide any tools to hold platforms accountable.

The result is a vacuum of responsibility, lack of transparency, no accountability, and a consistently growing number of cases of violence with no end in sight. When hate speech spreads or deepfakes go viral, victims have nowhere to turn. Platforms deny liability, and benefit from the high engagement this hateful content generates, which in turn brings more profit – reason why platforms like Facebook were found to be involved in inciting severe violence, including genocides, across the world, as they failed to control the dissemination of hateful content. Whereas, governments suppress speech instead of protecting it, as they continue to treat their own citizens as criminals who’d use civil liberties enshrined in the constitution and international human rights framework as their weapons. As a result, civil society and activists are left to pick up the pieces as they are targeted with baseless accusations, lack of funding, and intense scrutiny. In the meantime, the harms deepen, mutate, and multiply while victims and survivors continue to suffer the consequences of systemic failure.

The current trajectory that AI is being developed on is not unchangeable. It is shaped by choices made by companies, developers, regulators, and societies. But any reimagining of AI must begin with a confrontation of its harms, and must be done from an intersectional feminist lens that acknowledges the degrees and layers of societal marginalisation, its historic context and the future dilemmas. And we cannot build feminist technologies without dismantling the infrastructures that allow violence, hate, and exploitation to thrive. This requires recognising that AI, as it exists today, is not just a technical system based on some mathematics, coding and randomised data; rather, it is a political and economic project that serves the interests of a few, while exposing the many to risk.

In Pakistan, where the margins are already stretched thin, the stakes could not be higher. The gendered violence, digital repression, economic instability, growing political polarisation, and climate crisis, all converge to make AI a uniquely dangerous force. Its potential to amplify harm is unmatched, and its ability to do so quietly, invisibly, and at scale, makes it all the more insidious.

This is not a call for better AI, but a call to interrogate its foundations, to ask who benefits and who pays the price. To see AI not as a neutral advancement, but as part of a broader machinery of extraction, violence, control, and colonisation. As feminist and digital and human rights advocates, it is imperative for us to ask these questions, and to sustain that momentum that pushes for deeper structural change.