Right to a digital identity: Why are so many Pakistani women journalists forced to work anonymously? By Kinza Shakeel

May 14, 2025How Algorithms Silence Local Voices by Asma Tariq

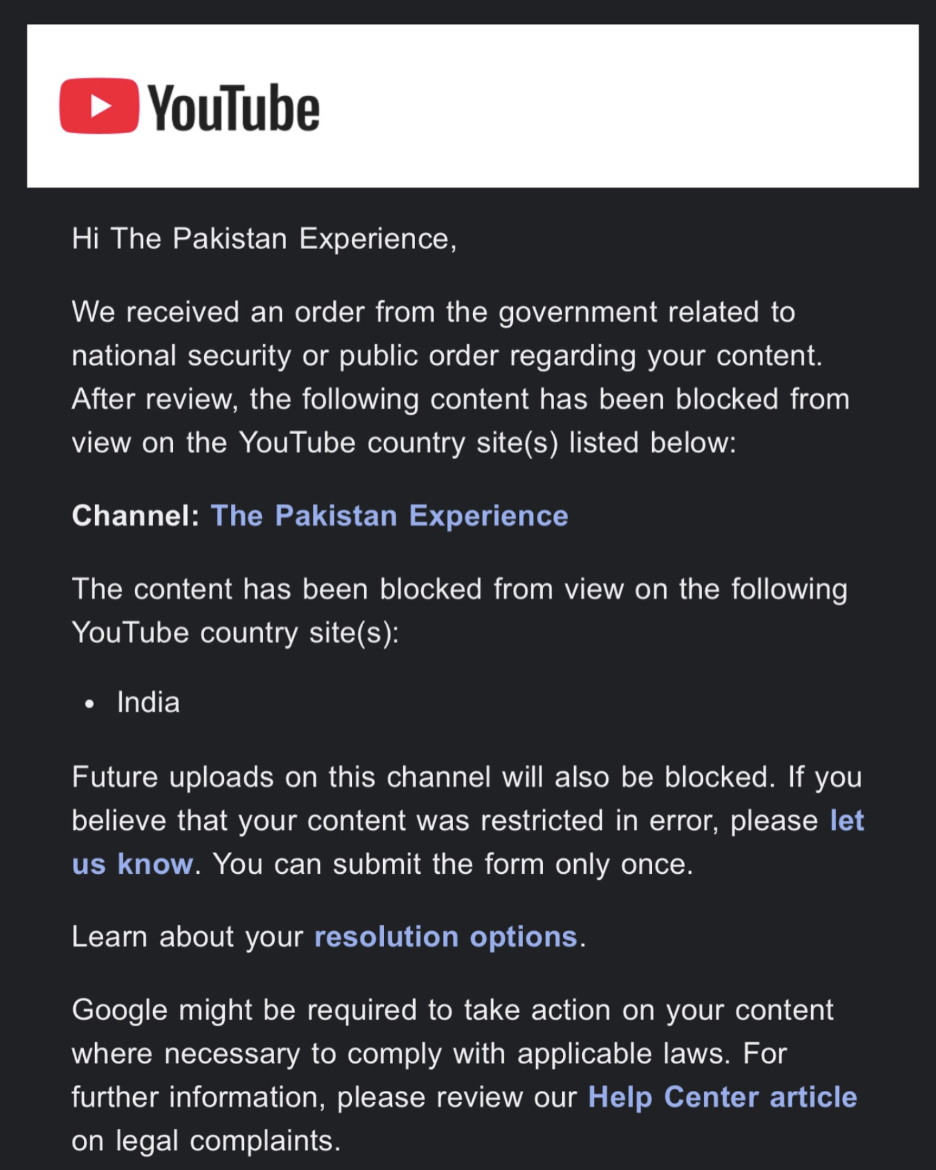

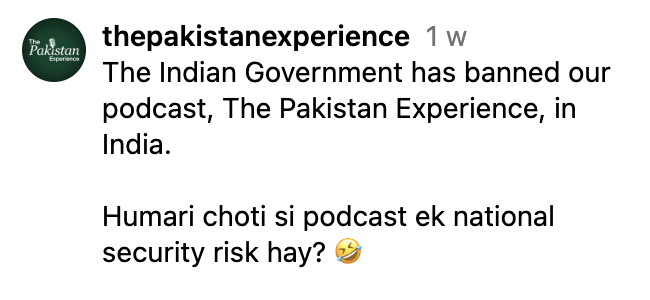

May 14, 2025On 28th April, The Pakistan Experience (TPE) – one of Pakistan’s most popular podcasts, hosted by comedian and content creator Shehzad Ghias Shaikh, took to Instagram to share that the podcast’s Youtube channel, where Shaikh hosts the full podcast was banned in India. The ban came following “an order from the government on national security or public order,” which means that TPE episodes can no longer be seen in India on Youtube. TPE’s account made light of the issue, questioning how a small individual podcast could pose a threat to an entire country, but despite being a joke, the question holds weight. After all, how does one podcast – or one podcast host – seem to pose a threat to the security of an entire country?

https://www.instagram.com/p/DI-ZUNMTK7B/

The answer here lies not in TPE or Shaikh alone, but in the changing culture that they are a part of where news and information is now being consumed beyond mainstream media channels. Even as mainstream news organisations have moved towards establishing their own digital presence, mistrust in the media in South Asia continues to increase as press freedom very obviously declines.

Over the last couple of years countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have seen crackdowns on journalists, a push for state narratives, and internet controls in an effort to control dissenting voices. This has become particularly obvious in light of the Pahalgam attack, which is what led India to block TPE’s Youtube channel along with 15 other Pakistani news related channels. The fact that TPE was considered to have the same impact as BOL or ARY news – both of which have been blocked – is a testament to the power of social media content and information – or “news-fluencers,” a term that many content creators now go by.

Dr. Erum Hafeez, Associate Professor and Head of the Media Studies Department at Iqra University shares that the role of these news-fluencers is becoming increasingly obvious in light of the Pahalgam attack. As Indian media continues to churn out state-sponsored narratives and dominate much of the global mainstream narratives around Kashmir, it is these news-influencers that citizens are turning to for an alternative viewpoint. “In today’s news cycle, stories don’t unfold — they collide,” Hafeez says. “One crisis barely finishes echoing before another demands our attention. Influencers, with their immediacy and intimacy, have learned to ride this relentless wave — and often, to steer it.”

This also comes at a time when media controls in South Asia have increased significantly. 255 cases of hate speech against minorities were recently documented in India and Pakistan ranked 152 out of 180 countries in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index. Earlier this year, after changes to PECA led to growing press suppression, journalists across Pakistan protested the controls. A PFUJ statement called the new changes “a policy of ‘carrot and stick’ is used to control the media, which has brought a few independent media houses to the brink of collapse.”

Amidst all of these changes, the rise of individual content creators and news-influencers who are providing alternative narratives to an audience that has for too long had access to heavily controlled media provides a sudden new reality – one that comes with its own benefits but also its challenges.

The “Influence” of Influencers

Sarosh Ibrahim, a digital creator and journalist with Maati TV, believes “this trend came about because of heavy censorship in media and journalism. A lot of platforms are now out of reach – so that led to an increase not just in influencers but also newer platforms.”

Speaking of the recent Kashmir incident specifically and the censorship we saw around it, a post by journalist Sahar Habib Ghazi went viral. Ghazi, outside the world of journalism is known for her instagram handle 2030mama, where she blends a mix of her nuanced news takes with her experiences and opinions on parenting, life and even women’s health – like raising awareness around and sharing her own experiences on endometriosis. Following the Pahalgam attack, Ghazi took to her instagram to challenge some of the misinformation and myths she was commonly seeing in the media. As a journalist of 20 years she’s established a certain credibility with her followers, but even outside of the media jobs she’s held, her own content has built trust with her followers and she’s maintained her stance when it comes to social justice, allowing her viewers to know where she’s coming from.

She also directed her followers to follow Stand With Kashmir, a non-profit organisation that stands with Kashmiri rights, further building on the network that social media has allowed her viewers to curate for themselves outside of the mainstream media narrative.

Sajeer Shaikh, a journalist and content creator shares similar observations regarding the Gaza crisis.

“Over the past few months, we have seen in real time how major news channels have succumbed to Zionist pressure, leading to some of the worst coverage of the war in Gaza perpetuated by Israel and the U.S. From the ashes of this disaster, many Gen Z influencers took to TikTok to share the other side of the story. In that case, yes, it is a fight against censorship and fascism,” she says, adding, “we have seen people break through the noise to tell us what’s happening. I would say it’s one of the finest examples of fighting censorship in modern times.”

And the content doesn’t always have to be serious or political, as Buraq Shabbir showcases with her culture and lifestyle stories. Speaking about the ways in which individuals generating content or running their own platforms impacts the way we consume journalism Shabbir says, “If I’m very honest I think it plays a very key role in how we consume media and generate content. Where publications have restrictions and limitations, this adds layers to the whole idea of those limitations.”

Hafeez also agrees, talking about the “influence” that these influencers have – changing the way many of us consume content and how we understand it.

“Without the guardrails of training or accountability, many influencers trade complexity for virality,” she warns. “In societies with fragile media literacy, it’s easy for the loudest voice to drown out the wisest one.”

Will Misinformation Become a Problem?

It’s scary because “When there is such development which is not regulated properly, it might cause more danger than giving benefit. When we talk about Pakistan, without any training, media literacy, without any background, or checks and balances, yes they are simply creating more noise,” Hafeez says. She’s careful to not paint everyone with the same brush, but does say that social media news can cause issues if people don’t know how to filter through it.

“Even if you click something by mistake once you’ll be bombarded by the same kind of news and it’s difficult to check it, or control it and then that content becomes your reality,” she says.

Aleezeh Fatimah, a journalist who’s worked for different news organisations – both offline and online – also points out that not every content creator is a journalist. “I don’t think journalists should be influencers. This is a very wrong trend that we have started because we do not really value journalistic integrity anymore, we just want views,” she says. Fatimah also adds,”very recently I resigned from a media organisation and came back to my old organisation, because the place that I went to was strictly confined to numbers, they were not paying attention to integrity or anything like that.”

For Fatimah, who calls herself “old-school”, and still prefers newspapers and news organizations, journalism needs to be about reporting the facts, not about “influencing people.” However, she admits that many people around her turn to social media for their news. “I think yes it can be more accessible but more democratic? I doubt that because there’s a culture of cult-following in our country,” she says.

Fatimah also believes that the trends she’s seeing in general can make social media more unsafe. “I don’t think we can fight censorship like this, instead I feel our social apps will keep getting restricted,” she says, adding, “This can put more people at risk because a lot of people from vulnerable areas and communities use social media.”

Shabbir doesn’t feel it’s as black and white as that. “Content creators don’t really fact check, don’t do the same kind of research, which is why misinformation is rising because a layman cannot decide whether this post is fact checked or its misinformation. You decide whether to be a credible person and what you want your audience to take, so I feel it varies from individual to individual,” adding that as a journalist she takes her own training and ethics seriously in the content and news that she puts out.

Making Information Accessible

When Ibrahim first started making content, she just did so because she wanted to make an impact, and then soon found her niche, focusing on body positivity, women’s issues and eventually going on to launch her own podcast called Dear Body. She shares that she did all of this because she couldn’t find anyone talking about these issues online at that time.

“I spoke about Pakistani women’s experiences, because online we had white women talking about white women’s experiences,” Ibrahim says, adding, “I thought if I can sit in front of the camera and give a one or two minute breakdown on what something actually means, not just reporting it but actually breaking down what it means.”

In her experience, creating both her own content and working for an organization, she finds creating for herself has a lot more freedom, as platforms often have to shy away from taboo or sensitive topics, being careful about the way they approach certain issues. “I feel when you’re creating for yourself you’re basically the CEO, you make all of the decisions, you’ve occupied all of the posts,” Ibrahim says while also adding that you can decide what kind of comments or backlash are ok for you to deal with and how much you want to push with your content.

Shabbir, who’s beat is culture and lifestyle reporting, says that where publications are limited in terms of the reviews they can share, she isn’t – and so she can often offer an alternate perspective to her audiences, which isn’t bound by PR or affiliations. She shares that she does a lot of reviews in her personal work because she finds that those are missing in more mainstream publications.

“I work with two online international publications and I’ve noticed that they focus on reporting not reviewing” Shabbir says, adding that one publication told her they can’t do reviews because as a publication they couldn’t show support for specific platforms or channels. However as an individual, she’s free to share her personal opinions over content she likes and dislikes, allowing her audience a view into whether or not that content may be for them, and understand it from a different perspective.

At the end of the day, whether we like it or not, the lines of content and journalism are blurring. “There is a bit of tension, I suppose, in being labeled an influencer when the word “journalist” carries more weight. I think that a journalist’s written word is them exerting influence, but the world has changed,” Shaikh says, also pointing out the content of prominent creators like Mysta Paki and Shehzad Ghias Shaikh. “Bilal and Shehzad do this at a much bigger scale. Bilal uses the power of visuals and storytelling to highlight pertinent issues and poses thought-provoking questions. Shehzad takes the bull by its horns through the power of conversation. Neither of the two are reporting, and that just goes to show how lines can be blurred as content evolves,” she says.

With social media giving everyone a voice, and both journalists and audiences increasingly disillusioned with mainstream media, it’s very clear that news-influencers are a reality that are here to stay. Who we as audiences decide to give that power to by considering them influencers may just be what decides how successful this new reality for journalism will be. For Hafeez, true influence is earned, not claimed. “It belongs to those who research with care, speak with responsibility, and carry the humility to admit when they are wrong,” she says, pointing out that she’s very careful with who she follows in this regard.