Digital Platforms, Environmental Journalism, and Censorship: Is Access to Truth Becoming Limited? By Samina Chaudhry

May 14, 2025Newsfluencers by Anmol Irfan

May 14, 2025 Trigger Warning: Following contains mentions of violence against women.

Trigger Warning: Following contains mentions of violence against women.

Note: All the names used are pseudonyms to protect the privacy of the female journalists.

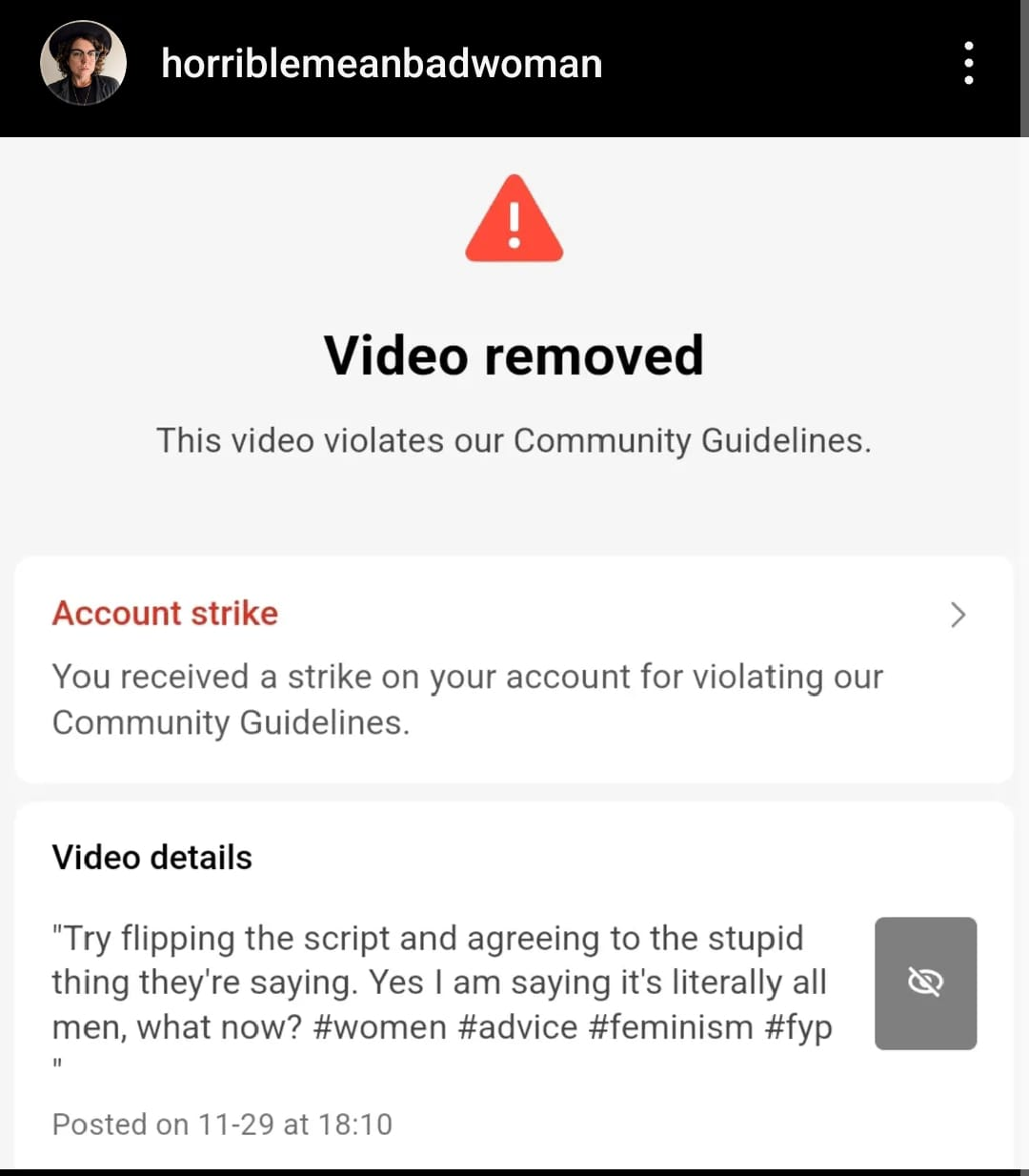

Caption: A representational illustration depicting the situation of freedom of expression and speech for Pakistani women journalists. Source: Made by writer.

It was 3am midnight when a myriad of phone calls started ringing while Zeba remained immersed in a sound sleep without a worry about her life and safety.

She could still remember the relief she felt a day before when she went for a little ice cream date with her friend after a long day in the newsroom.

As she picked up the call, a deep male voice called her randi (whore) and threatened to rape her on gunpoint if she didn’t delete her social media posts in support of a minor girl, who became a victim of sexual violence in a local hospital.

Zeba has been a vocal supporter of Pakistani women, especially those belonging to the minority Hazara and Afghan communities. She had been amplifying their causes on her X, formerly Twitter, account for years. With time, she became a popular voice for these women.

This wasn’t an isolated event; Zeba often posted for women’s rights as a journalist and has continuously faced backlash for her posts not only from the right wing but also from the journalist community as well.

The case of the minor girl became a turning point in Zeba’s life as a female journalist in Pakistan. She had to let go of her public identity and profile because of the danger to her life. “My crime was that I dared to criticize the violence that Pakistani women have to face on a daily basis,” said Zeba, an accomplished journalist based in Karachi.

As she was recalling what happened to her, it wasn’t easy for her to describe her experience with those phone calls. She was shivering not only out of fear but considering it was traumatic to hear a man call you a “whore” in the middle of night and threatening you with rape, Zeba faced more than just an ordeal.

“I was backing that little girl’s case; she had no family, no external support and her abuser was a powerful man. Someone had to stand up for her,” she said.

The phone calls she received were from male friends of the abuser and though she didn’t want to take down her social media posts in support of the girl, she had to as soon as she was doxxed.

Notably, doxxing is the act of publicly spreading personally identifiable information about an individual or organization, usually through the internet and without their consent.

“That incident forced me to go anonymous online because speaking for justice gets you killed in Pakistan. I continued supporting that girl by raising funds for her treatment and education but she deserved more, just like thousands of other Pakistani girls and women,” Zeba added.

Going anonymous after years of being a prominent female journalist who amplifies women’s rights wasn’t easy for Zeba. However, Zeba’s story is one of many women journalists in Pakistan, who have been deprived of their right to a digital identity just because of their work, opinions and, most importantly, their gender.

Why choose anonymity?

Women journalists aren’t working anonymously because they don’t have the guts to show their real identity. Instead, they are forced and coerced into hiding due to an unsafe digital environment that doesn’t make any space for their voices.

“As a journalist and social activist, I’ve had to make the difficult choice to remain anonymous—not because I lack courage, but because the cost of visibility for women like me in this society can be devastating. The risk is not just digital backlash and endless bullying, it’s also real-world consequences: isolation, character assassination, threats, and even violence,” said Zehra Afsana, an anonymous female journalist based in Sindh.

Though with the rise of social media, the critical issues surrounding women’s rights and violence against religious and ethnic minorities, have achieved a space of their own that they couldn’t get in mainstream television and radio before, still journalists, especially women, who speak up for such issues can’t do it freely because of online mobs, biased policies and general non-safety.

Highlighting this dilemma, Sehar, another anonymous female journalist said: “I am not afraid of showing my face but there’s a reason why I have to hide my identity. I have spoken a lot against religious persecution of women in this country and in one instance, when I posted about this issue on X, I got a text message from PTA (Pakistan Telecommunication Authority) accusing me of blasphemy and warning me to not post such content on social media otherwise there’d be consequences.”

Alia, who has been raising her voice for gender-based violence in Pakistan, also raised the same concerns related to her anonymity.

She said: “I choose anonymity as a refuge in order to protect myself and my family. It’s dangerous to be visible in this country for daring to dig a little bit out of the box. I don’t want to stop speaking up — I can’t do it under my full name anymore because that’s not a practical solution but I’m going to continue to speak out for those who can’t.”

Another prominent reason for these women journalists choosing anonymity are the social norms and patriarchal expectations put on them by both their families and society. Zehra spoke about this aspect as a Sindhi woman: Coming from a “place where patriarchy isn’t just a social norm but an inherited legacy,” voicing an opinion as a woman is often seen as a threat, even a dishonour. Although she has moved to a bigger city, the weight of izzat (honour) tied to her family name and community still follows her.

“Every word I speak, every post I write, every cause I support is scrutinized through the lens of respectability politics,” she added.

Lack of Safety in the Digital-verse

Just like society defines the larger fabric of our real lives and what should or shouldn’t be considered normal, the digital space also ends up following the same pattern, mirroring our physical world. People amplifying and backing problematic ideologies in real lives also exist in the digital-verse and as technology advances with each passing day, we see the same framework replicated in the digital world.

According to a report by the International Journalists’ Network, women journalists are frequent targets of harassment particularly on social media. The abuse is not limited to digital media; many journalists are also threatened with physical assault as well as offline violence, the report mentioned.

Benazir Shah, a prominent journalist affiliated with Geo News Network, encountered online trolls for her Covid-19 reporting, when she questioned the reliability of the government’s data.

Another well-known journalist, Shiffa Yousafzai, who has worked as a news anchor and a columnist, faced personal attacks on social media after she made some political comments on her morning show.

These incidents amongst many more are a testament to the fact that women journalists in Pakistan are discriminated against and particularly targeted for their speech online.

Women journalists turn towards anonymizing themselves in online spaces for their safety and security. Upon interviewing 5 women journalists for this piece, some common patterns have been identified as to why women anonymize themselves in online spaces.

Normalized Sexism

Pakistani women journalists are subjected to misogynist slurs, threats, harassment and bullying on a daily basis.

“Online platforms tend to be sexist, with women being harassed and their content censored,” said Alia.

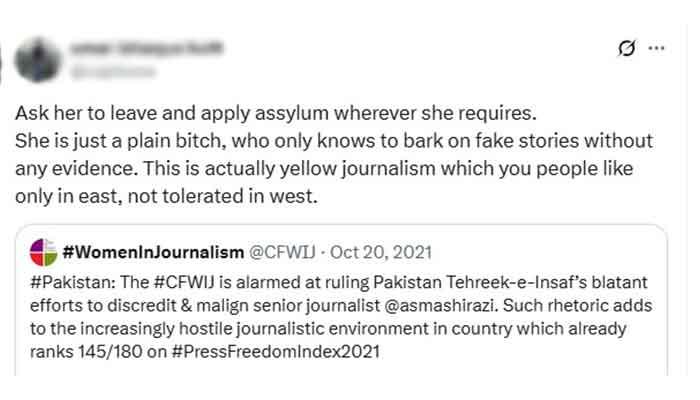

The screenshots above are examples of how misogynist slurs like “bitch” and “prostitute” are normally used to attack female journalists. In this particular incident, right-wing political party supporters bashed anchorperson Asma Shirazi, in response to a post on X by the Coalition for Women in Journalism (CWFIJ) in support of her and opinions. Slurs like this have become all too common, making it easier for people come after women journalists on digital media platforms.

Caption: A video thumbnail spreading misinformation and using abusive language against women attending Aurat March. Source: YouTube.

Misinformation against women journalists is also a common practice to malign and target them. Misleading and false thumbnails like the one attached above still remain on social media platforms despite being a clear attack on Aurat March organizers and marchers.

Witch Hunts and Online Mobs

There has also been a rise of online mobs who plot witch hunts against Pakistani women journalists from time to time by publicly maligning and degrading them with impunity.

Popular anchorpersons Gharida Farooqi and Asma Shirazi have been at the forefront of facing these attacks for years. Women Press Freedom, a support organization, has documented a dozen troll campaigns against Gharida Farooqi since at least as far back as 2020. More recently, in 2024 television personality Dr Omer Adil spewed derogatory remarks against Farooqi during an online vlog. Following the journalist’s complaint, he apologized to her.

In the video apology uploaded to YouTube, Adil said: “This is an apology from my side. Dr Omer Adil to the host and anchor person Gharidah Farooqi.”

He added: “This is completely an unconditional, whole hearted and sincere apology. I understand she was hurt and distressed by a podcast which was edited and completely manipulated by the host of the podcast. I have no grudges… It is a sincere and unconditional apology. Thank you so much.”

Asma Shirazi has also been the target of consistent online attacks against her by supporters of political parties. She endorsed a counter-petition led by the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) to call out the normalized harassment against female journalists. Network of Women Journalists for Digital Rights (NWJDR) termed the attacks against her as a gendered disinformation campaign.

Caption: A post of journalist Asma Shirazi after she was targeted by online mobs. Source: X @asmashirazi

There have also been incidents when women journalists reporting issues pertaining to religious and gender minorities are subjected to religious persecution, and in extreme cases blasphemy accusations.

Allegations like these make women journalists vulnerable to physical incidents of violence which have been all too common in the country in the past.

“Verbal harrasment, acid attacks, rape threats and death are the most common responses by men. In a country like Pakistan, where mobs gather and lynch people on fake allegations of blasphemy and where women’s rights are considered a threat to religion, we as women can’t even imagine what a mob of angry men would do to our bodies, if we ever get falsely accused of blasphemy for merely defending women’s rights,” said Chandni, another young journalist, disclosing the harsh reality of witch hunts that women journalists have to face online.

Deepfakes and Censorship

Artificial intelligence has further exacerbated the situation of freedom of expression in the country, especially for women journalists. Deepfakes, superimposing someone’s picture onto a video or digitally altering images to create fake scenarios, have become a common tactic to shut off and silence women journalists through psychological abuse. Perpetrators create fake images of women journalists and spread them in order to smear their reputation.

This negative use of technology has targeted common women as well as influential politicians like Maryam Nawaz and Azma Bukhari. For women journalists, deepfakes have been defined as an online war.

Caption: A post informing about deepfakes used to target politician Azma Bukhari. Source: X@theasianfmnst

On the other hand, many women journalists and activists also face censorship.

“Feminist content continuously gets restricted, flagged or shadow banned because it offends misogynists,” said Chandni, adding that in contrast sexist and hateful content exists freely, even after people report it.

Community guidelines on the digital platforms are very vague. Most of the time, a post can be calling out violence against women but the platforms find it offensive on the basis of its engagement outcome.

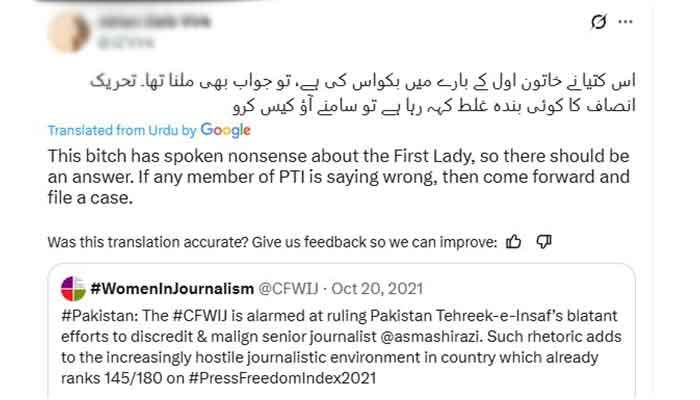

The screen attached above shows the same bias. Content posted by feminist activist @horriblemeanbadwoman on Instagram saying “all men” was removed, even though it was an effort to call out misogyny online. Many women are subjected to the same discrimination as platforms deem their posts to be violating community guidelines.

Moreover, in many cases, authorities remove women’s content, where they are expressing themselves freely, on the allegations of promoting “immorality” or “vulgarity”.

Tech accountability

Algorithm bias

In addition to community guidelines and censorship, algorithm bias is evident across digital media platforms. Women journalists interviewed for this piece have noted that content that targets the sentiments of women and minorities receives more engagement, with algorithms pushing it further.

“Social media algorithms often amplify misogynistic content made by men, rewarding controversy and engagement. Such posts gain more reach, likes, and visibility, while feminist voices, especially from women are frequently suppressed, reported, and/or shadow-banned, reinforcing harmful gender biases online,” said Alia.

Caption: A screenshot of an article on social media influencer Andrew Tate, whose abusive posts receive a lot of engagement and are favoured by the algorithm. Source: The Guardian.

Alia’s concerns were also echoed by Zehra. She said: “There was a time when my feed was flooded with sexist memes—like the most viral was two men sipping tea saying “women” over a joke about bad driving. When a woman makes a mistake, it’s blamed on her gender; when a man does, it’s just a human error.”

Zehra also added that podcasters, usually men, openly use derogatory language for women and easily rack up millions of views. The algorithm rewards content like this with reach and engagement. Yet, if a woman responds with a comment as simple as “men are trash” under a post showing blatant abuse or sexism, she immediately gets banned.

This double standard makes it clear that platforms often enable misogyny while punishing women for reacting to it, she said.

In 2017, Facebook banned women users for writing “men are scum” and “men are trash” comments, deeming them as “hate speech”. Women, who wrote these comments, asserted that they did so to call out misogynist violence online, while content by self-proclaimed “misogynist” influencers like Andrew Tate face no hindrances with platforms amplifying violence against women.

No specific way to identify harmful content

Social media platforms have played a vital role in amplifying the voices of rights movements but they also take content and accounts down on the basis of the algorithm and mass approval. This is also the reason why so many female journalists’ accounts have been taken down, mainly because their work and opinions did not sit right with the algorithm favouring the majority.

Across the globe it has been noted that women journalists and activists accounts have been taken down or shadow-banned when their content was misinterpreted as offensive. Conversely, rape jokes, misogynist memes, violent videos, and genocidal ideas to name a few continue to exist on these platforms.

It is worth noting that male journalists also face backlash on online platforms. However, it is not as drastic as it is for female journalists, as they encounter heighted gendered abuse in digital spaces as compared to their male counterparts.

The importance of a face

The right to a digital identity is important but many women journalists don’t have this right, rather it has been taken away from them due to the hostile and biased environment online. To be able to express your opinion with your face and real name is a liberty, a privilege that unfortunately several Pakistani women journalists don’t have.

According to many of them, if the digital environment was safer, they would not stay anonymous.

“I’m protecting myself from extremists who’d accuse me of blasphemy and who could potentially restrict my freedom to leave the country because of my feminist views. But once I’m in a safer environment, I’ll ditch the anonymity and speak my mind freely, even if it means dealing with online trolls. I’m not intimidated by misogynists trying to silence me. Women get cyber bullied and attacked for their opinions, expression, and choices all the time, and it’ll keep happening if we don’t do something about it,” said Sehar.

She also put forward the idea that women journalists in comparatively safer countries, specifically in the West, who are privileged enough to be safe should take a stand for women journalists in the global south and give them support.

As people don’t engage with fake accounts or anonymous pages the same way they do with real individuals, we need women who can be visible, heard, and relatable. It won’t be easy – we might get attacked or vilified – but someone has to take that first step. If we do, it’ll give other women the confidence to express themselves, and that’s how we can start changing the digital landscape and making it safer for all of us, she added.

Probable solutions and safer platform

Not engaging with misogynists, trolls and haters online, blocking and reporting them or even changing your gender online are some of the solutions used by women journalists in order to protect their online presence from harassment and censorship. Although these are not long term solutions, they do provide women with some semblance of safety in online spaces.

Certain platforms are necessary to raise issues. For instance, if someone wants higher government officials to take action on gender–based violence, then they have to raise the issue on X, even though it also has a history of not holding misogynist trolls accountable.

No social media platform is completely safe and people have different preferences as per their needs and use.

According to the women journalists interviewed for this piece, they use different platforms as per their own priority for safety. Some find Instagram more safer than TikTok, Facebook and X, while some consider Facebook and WhatsApp more secure. Some even said that Pinterest is the safest social media platform as it is used by women more. Others also mentioned that they use Tumblr for their work.

“I have one question for these tech platforms: How do you allow blatant misogyny and violent stereotypes to thrive, yet act instantly when a woman responds out of frustration or pain? This double standard speaks volumes. It’s not just negligence, it’s complicity,” said Zehra emphasizing that sometimes, at best, a comment might be removed but the threats don’t end there, they continue in direct messages, and reported accounts are often ignored.

Pakistani women journalists are entitled to freedom of speech and expression in the digital realm. Social media platforms need to ensure that they make a safer environment for vulnerable and marginalized genders and professions to ensure it is a safe space for all.