How Algorithms Silence Local Voices by Asma Tariq

May 14, 2025SILENCED ALGORITHMS: How Platform Policies Shape Narratives & Suppress Marginalized Voices in Pakistan by Aneela Ashraf

May 14, 2025In early 2024, a fake, sexually explicit AI-generated video depicting Punjab Information Minister Azma Bukhari circulated widely across Pakistani social media. The deepfake, reportedly disseminated by PTI activist Falak Javed, triggered immediate public outrage. Azma Bukhari promptly filed a formal complaint with Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) under the cybercrime laws, demanding an inquiry into the creation and spread of the doctored content. The incident was a chilling reminder of how artificial intelligence (AI) is fueling a new era of misinformation in Pakistan, one where the boundaries between truth and falsehood blur rapidly.

Just weeks later, another deepfake targeting Bukhari surfaced, showing her allegedly making derogatory remarks against political opponents. Although fact-checkers, including Soch Fact Check, quickly debunked the video, it had already reached millions, highlighting how synthetic media can hijack public opinion before verification mechanisms can catch up. Such attacks are no longer isolated. High-profile political figures, particularly women, have increasingly become the targets of AI-generated disinformation.

One of the most alarming episodes involved an AI-manipulated video portraying Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) leader and Chief Minister Punjab Maryam Nawaz meeting UAE President Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan during his official visit to Pakistan. The fabricated footage insinuated secret political dealings, sparking widespread speculation. Despite Soch Fact Check’s detailed investigation confirming the video’s fraudulent nature, the damage was already done. FIA later arrested several individuals linked to the dissemination of the doctored clip, but experts say that mere reactionary measures are no longer enough.

“Pakistan, a state known for weaponising laws, has used anti-terrorism, anti-narcotics, and cybercrime (PECA) laws to suppress independent journalism and political dissent,” said independent journalist Asad Ali Toor in a conversation with Digital 50.50. “I have no doubt that the state will use AI-driven fact-checking and monitoring to target journalists critical of the regime. Even minor errors will be punished harshly and not just to silence the individual, but also create a chilling effect across the entire journalistic community,” he added.

While traditional fake news often involved basic manipulation like misquoting leaders or crudely editing images, today’s challenges are far more sophisticated. “The emergence of AI, particularly deepfakes and synthetic media, has added fuel to a fire that was already out of control,” said Asad Baig, Executive Director of Media Matters for Democracy (MMfD). “Previously, creating convincing fake content required high technical expertise. Now, with basic access to AI tools, even an amateur can generate hyper-realistic videos, audio clips, and images that can deceive even the most discerning audiences,” he explained. The scale of the problem is staggering.

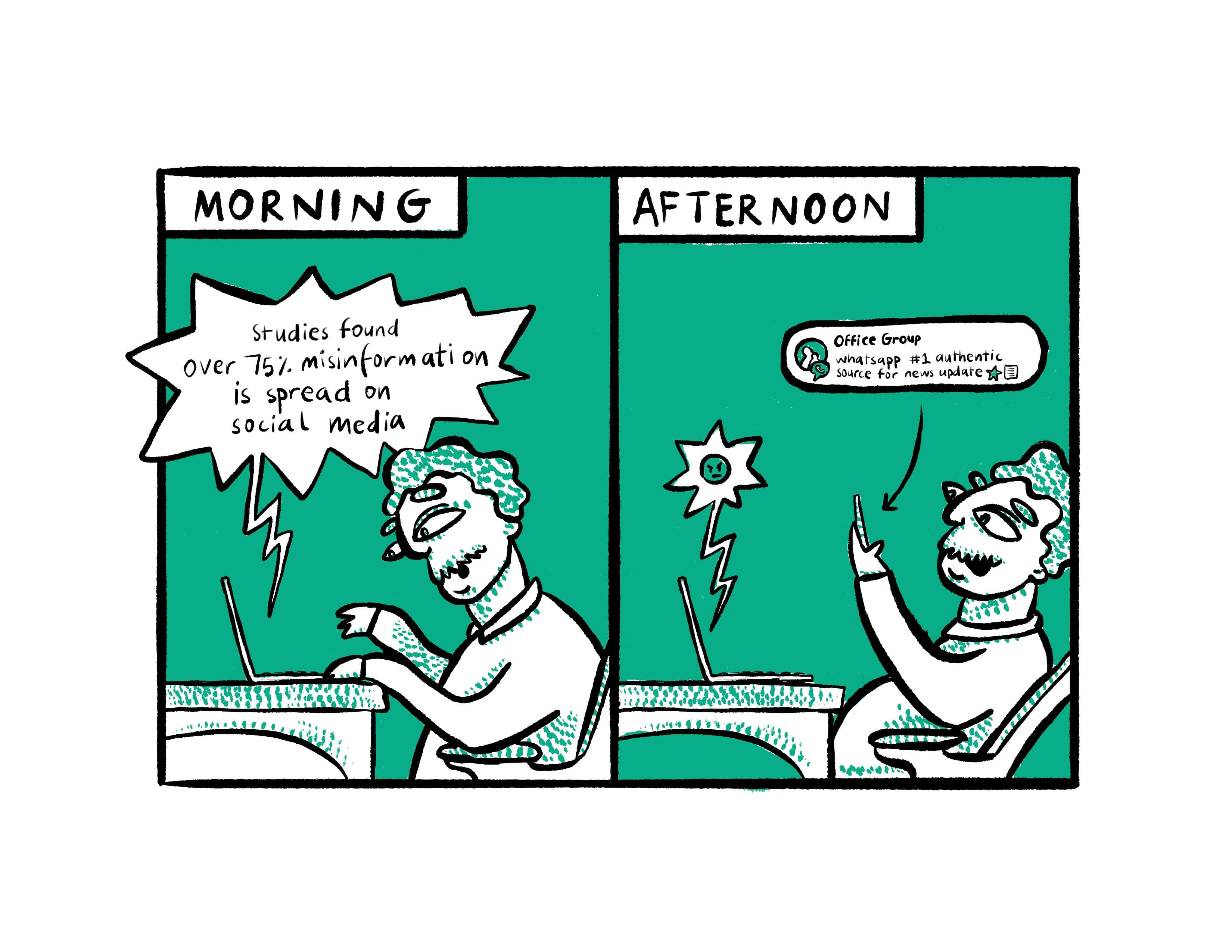

According to a 2023 report, “Fact Checking and Verification: Navigating the Misinformation Landscape in Pakistani Newsrooms and Beyond,” by Media Matters for Democracy, over 75% of viral misinformation in Pakistan originates from social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok. These platforms are primary news sources for many, yet they often lack mechanisms to ensure the accuracy of disseminated information.

Fact-checkers are struggling to keep pace, even with the help of AI-powered tools like InVID, Deepware Scanner, and reverse image search engines. Yet these tools come with major limitations. “Fact-checking in Urdu and regional languages isn’t particularly challenging visually, because we use AI mainly to detect anomalies in images and videos,” said Fayyaz Hussain, Senior Sub-Editor at Geo Fact Check. “However, verifying audio-based misinformation is a different beast altogether. You can’t look for visual signs in an audio clip. A convincing fake voice recording can spread like wildfire before there’s even a chance to verify it and often, original recordings for comparison simply don’t exist.” Hussain further emphasized that voice-based misinformation, such as fabricated speeches by political leaders, poses a greater verification challenge because few AI tools are capable of analyzing the linguistic nuances and tone subtleties of Urdu and other local languages. This linguistic gap is a critical vulnerability, underscored by academia as well.

“AI-based fact-checking software is still largely ineffective when it comes to Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, or Balochi,” said Dr. Ayesha Ashfaq, Chairperson of the Department of Media and Development Communication at the University of Punjab. “Most of the verification algorithms are optimized for English and fail to catch the nuances, sarcasm, and cultural idioms that characterize communication in Pakistan.” As a result, fact-checking organizations like Soch Fact Check, Dawn’s fact-checking desk, and The News’ fact-checking initiative continue to rely heavily on human analysis, a resource-intensive and time-consuming process. Adding another layer of complexity is Pakistan’s low media literacy rate. Dr. Ashfaq pointed out that despite a massive surge in social media usage, critical thinking and fact-checking skills among the general public remain dangerously underdeveloped. “Urban, younger, and educated populations show some level of awareness about misinformation, but in rural areas, awareness is almost nonexistent,” she warned. The stakes are even higher because universities, which should be training the next generation of journalists, have been slow to adapt. “While a handful of universities have introduced workshops on deepfakes and media manipulation, there’s no uniformity, and certainly no mandatory curriculum integration,” Dr. Ashfaq said. “Many journalism students graduate without ever encountering a course on identifying or combating AI-based misinformation, a critical threat to the future of journalism.

” AI’s integration into everyday digital life is accelerating. “Whether it’s creating memes, editing videos, or transcribing interviews, AI is no longer some futuristic tool; it’s embedded in how we communicate and consume content today,” said Yasal Munim, Senior Manager, Programs at MMfD. “But greater access to AI tools has also democratized the ability to produce misinformation.” Munim cited recent examples where AI-generated voices of incarcerated political leaders were used to address rallies or mobilize voters.

During the tense Pakistan-Iran airstrikes in 2024, deepfake videos flooded social media, sowing panic and confusion at a speed that fact-checkers simply couldn’t match. “The velocity at which misinformation spreads during such sensitive events means that fact-checking becomes a rear-guard action by the time the truth is clarified, the falsehood has already taken root,” she explained.

Gendered disinformation is another particularly dangerous frontier. “Women politicians and activists are disproportionately targeted with AI-generated deepfakes that are sexually explicit or aimed at damaging their honor,” said Munim. “Such attacks are designed not just to humiliate individuals but to deter women’s political participation altogether.”

Despite the severity of these threats, Pakistan’s regulatory framework remains woefully outdated. Laws such as the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) were crafted in an era before AI-generated misinformation became a mainstream issue. Instead of evolving to meet these new challenges, critics say, PECA has often been misused to curb dissent and silence journalists.

“PECA was never designed to tackle synthetic media or deepfake threats,” said Asad Baig. “Instead of being reformed to address real dangers, it has become a blunt instrument for censorship.” Baig stressed the urgent need for new, rights-based AI regulations that protect freedom of expression while simultaneously addressing the complex dangers of AI-driven disinformation. “We need enforceable data protection laws, transparency in algorithmic decision-making, and strong independent oversight bodies to ensure that countermeasures don’t become tools of political oppression,” he said.

Yet, amid these challenges, there are seeds of hope. Baig pointed to initiatives like Facter, a collaborative verification tool that aggregates verified content and leverages AI to assist fact-checkers and newsrooms. “If we can empower journalists with the right AI tools to enhance verification, storytelling, and audience engagement, journalism in Pakistan can become faster, deeper, and more resilient,” he said. However, experts unanimously agree that foreign AI tools alone are not enough. “Without localized research and AI solutions that understand Pakistan’s unique sociopolitical and linguistic contexts, we will always be fighting an uphill battle,” said Dr. Ashfaq.

Munim echoed this, emphasizing that the pathways through which misinformation spreads and the ways audiences interpret and react to it differ significantly between urban and rural environments in Pakistan. “Understanding these social dynamics is crucial if we want to build effective defenses against disinformation,” she said.

As Pakistan approaches future elections and becomes increasingly digitized, the consensus among experts is clear: Without urgent action to educate the public, empower journalists, strengthen fact-checkers, and develop localized AI defenses, the credibility of journalism and the health of democracy itself will remain under grave threat. “Disinformation isn’t just about lies anymore,” warned Asad Baig. “It’s about dismantling the very ability of people to trust anything they see or hear.”

The deepfake era is here and unless Pakistan rises to the challenge, truth itself may become the first casualty. The MMFD report sheds light on Pakistan’s weak fact-checking infrastructure. Alarmingly, only 1 in 10 journalists reported having access to digital verification tools within their newsrooms. Meanwhile, approximately 46.7% of journalists confessed they had never received any formal training in fact-checking. This gap leaves the media sector vulnerable to manipulation, especially as disinformation tactics become increasingly sophisticated.

A major obstacle in combating misinformation is the language and technology gap. Most AI-based fact-checking tools are designed primarily for English content and struggle to effectively process Urdu, Pashto, Sindhi, and other regional languages. Furthermore, voice-based deepfakes present a particular challenge, as the technological tools required to verify manipulated audio clips are severely limited in Pakistan. Press freedom has also come under increased threat under the guise of combating fake news. Laws such as the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) and new regulations like the Punjab Defamation Act 2024 are being weaponized to silence dissent instead of genuinely addressing the spread of disinformation. Journalists and critics have faced heightened harassment, surveillance, and arrests, creating a chilling effect on freedom of expression.

The rise of AI technologies has brought new risks into the media landscape. These tools enable the rapid creation of hyper-realistic fake content, making it easier to deceive the public. Particularly concerning is the growing trend of gendered misinformation targeting women politicians and activists, often through the creation of sexualized deepfakes intended to intimidate and discredit them.

Adding to these challenges is Pakistan’s digital literacy crisis. Low levels of media literacy have made the general public extremely vulnerable to false narratives. Common hoaxes such as fake government notifications regarding public holidays, petrol prices, or official decisions continue to circulate widely on social media, often without scrutiny.

In response to these worrying trends, MMfD recommended several strategies to strengthen Pakistan’s defense against misinformation. These include investing in AI forensic tools tailored for multilingual analysis, training journalists in digital verification and AI literacy, and promoting community-based collaborative fact-checking initiatives. Crucially, they also emphasize the need for regulations that protect freedom of speech while combating disinformation and call for integrating critical thinking and media literacy education into school and university curricula.

Similar concerns are echoed in the International Media Support (IMS) report, which further explores the role of digital platforms in spreading disinformation. The report highlights that social media has become the main conduit for the dissemination of misleading information, which has endangered public health, political stability, human rights, journalism, and peace in Pakistan. The IMS study notes that Pakistani journalists are at the frontline in the fight against disinformation but face a host of challenges. A lack of conceptual understanding of how disinformation operates, combined with the monetization of sensationalist content, limited financial resources, language barriers, and political pressures, has severely hindered fact-checking efforts.

The environment has become even more toxic as online harassment campaigns and financial instability discourage independent journalism. To counter these challenges, IMS recommends enhancing fact-checking practices, offering regular training for journalists, building coalitions among media outlets, and improving media and information literacy among the public. The report stresses that only a collective, informed, and well-resourced effort can reverse the tide of misinformation and safeguard democratic values.

According to the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF), the 2024 general elections in Pakistan witnessed a significant rise in disinformation, much of which was powered by AI-generated content circulating across major social media platforms. These AI-driven falsehoods not only misled the public but also posed a serious threat to the integrity of the electoral process.

Recognizing these emerging challenges, Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Atta Ullah Tarar, recently emphasized the urgent need for developing an ethical framework to guide the responsible use of AI technologies. Such a framework is vital to counter the growing risks of AI-driven disinformation while encouraging innovation that supports transparency, accountability, and democratic governance.

Baig believes that AI has the potential to either deepen the crisis journalism is already facing or to become a powerful force for renewal and empowerment. At Media Matters for Democracy, we are focused on the latter i.e. working directly with journalists and newsrooms to infuse AI into journalism processes in ways that strengthen reporting, not replace it.

We believe the real promise of AI lies in how it can be used to automate repetitive tasks, analyse massive datasets, surface hidden patterns, and support investigative work that would otherwise be overwhelming given the resource constraints so many Pakistani newsrooms face. If we empower journalists to use AI as a tool for efficiency, verification, storytelling, and audience engagement, while maintaining standards, it can help journalism become faster, deeper, and more resilient.

But if AI is left unchecked, used purely for clickbait optimisation, or misused to spread synthetic misinformation, it could cause real harm, further undermining trust at a time when journalism urgently needs to rebuild it. Asad Baig stated, “Our efforts at Media Matters for Democracy are aimed at ensuring that AI is seen not as a threat to journalism, but as an empowering tool that, when used thoughtfully and ethically, can help journalism thrive in Pakistan over the next five years.”